Set in a world eerily similar to our own Covid-19 induced reality, The Migration is the perfect pandemic read.

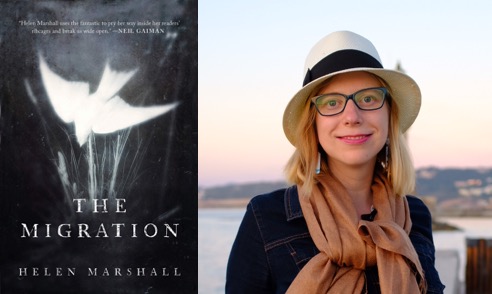

In The Migration by Dr Helen Marshall from the School of Communication and Arts, a strange new illness ravages the globe, hitting the youngest the hardest. All seventeen-year-old Sophie Perella wants is to protect her baby sister Kira but after the worst happens and Kira dies, Sophie finds she herself has the same condition. Now she must discover the cost of adapting to this dangerous new world.

What inspired you to write this novel?

In the winter of 2002 – my final year of high school, when I was seventeen, the same age as Sophie in The Migration – a tanker truck slammed into the side of my dad’s car at an icy junction within sight of the chemical plant where he worked. He survived with minimal permanent injuries to his body, thank goodness – but in the collision he suffered a catastrophic head injury that compromised his short term memory, a condition that he still struggles with today.

This crisis had a profound effect on me. In the weeks that followed, myself and my younger sister Laura were alone, completely dependent on one another. Our mom was in South Africa, tidying up her own mother’s affairs, and while my brother came down several times to check on us, he couldn’t stay for more than a few days. Laura and I became close over this time – tremendously so – and when I left for the University of Guelph six months later, a year later she followed after me. Through the difficult years of my graduate work, Laura supported me tirelessly, letting me cover the walls of our shared apartment with post-it notes as I finished my PhD in Medieval Studies at the University of Toronto and bringing me coffee during late-night writing sessions. But as 2013 came to an end we both knew that things were going to change. I had just accepted a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Oxford to study manuscripts written during the time of the Black Death.

The emotional core of The Migration came out of that sense of what it means to go through a major transition in life. How it feels to know your life is diverging from someone whom you care for very greatly, how scary change can be – even if it turns out to be a good thing.

My dad’s accident had another effect which spurred on the writing of this novel: a lifelong interest in the idea of history and what it means to remember – to bury something in your mind so deeply that it becomes a part of you. This manifested itself in a passion for medieval literature that became the subject of my PhD. What fascinated me about the fourteenth century was that it was an age of true crisis, one of the few moments in history when the human race teetered on the edge of extinction as a result of the Black Death. And yet in the literature of the period, it was hardly ever mentioned. It was a strange, blank space, as if the poets of the age were struck by amnesia. I was also fascinated by the fact that despite the devastation, when scholars write about the effects of the Black Death, many of them are seen as positive: the social upheaval led to wage increases and a consolidated sense of English identity, even the resurgence of English poetry, in general. For those who survived the crises of the fourteenth century, the terrible loss of human life, there was hope.

The stories of the fourteenth century resonated for me with the current narratives of massive upheaval that we regularly hear today—economic frustration and international instability, the rise of global health scares such as Ebola virus in 2014, the Zika virus and of course, shockingly Covid-19 at the present moment—the fear of ecological tipping points already passed and the simultaneous hesitation to acknowledge this might be true. There is a sense that we are living through our own age of crisis.

What did you learn from The Migration?

In The Migration I wanted to draw together these two threads, personal and societal trauma. But rather than following a narrative of apocalypses, I wanted to find a way to cast these transitions in a more hopeful light, recognizing how difficult it can be to leave behind a way of life but also searching for a way to understand that who we are, what we are is always in transition and always has been, as history attests.

In an excellent article in the Boston Review titled “What Disasters Reveal”, author Junot Diaz used the devastating earthquake which struck Haiti in 2010 to reflect on insights disasters provide into the underlying conditions of apocalyptic events. He reminds us of the Greek etymology of the word apocalypsis, meaning “to uncover or reveal”. This understanding of apocalyptic literature has shaped my approach to writing over the last five years. Blending the fantastic and the scientific, my writing has encouraged readers to become aware of the dangerous conditions undergirding the Anthropocene era even as it refigures those conditions as a catalyst for embracing necessary positive—if radical—change.

Just as I learned in 2002, I wanted to show that at the heart of what it means to survive trauma must be extraordinary compassion: a willingness to be changed even as we find that the ones we love are changing.

What advice do you give to your students looking to undertake this type of writing?

Crises are unpredictable. The post-apocalyptic genre has furnished us with a range of disaster tropes, from the endemic violence of The Walking Dead to the oppressive politics of The Hunger Games. Yet in genuine crises we see the potential for extraordinary courage, resilience, sacrifice and social cohesion. When writing The Migration I was particularly inspired by a little town called Eyam in Derbyshire, England. It survived the worst of the onslaughts of plague in the fourteenth century untouched, only to fall in 1665 after an infected parcel of cloth arrived from London. The villagers created a perimeter of boundary stones, which no one was supposed to cross. A quarantine. They bored holes in the rocks where they left coins soaked in vinegar in return for bundles of meat and grains from their neighbours. This story reminded me that when the world seems to fall apart, people can pull together. So I suppose my advice would be to observe the world around you, draw from history, and aim to include the whole range of human behaviours--selfishness, cruelty, stupidity but also kindness, resourcefulness, and compassion.

At the School of Communication and Arts, we know that learning to write well is about more than mastering craft. It is about finding a purpose and a voice, building bridges through language, and entering a conversation that has been going on for centuries, between diverse cultures and across countless generations.