Creative writing and national security

Creative writers are word mavericks. They breathe life into new worlds, grip readers with carefully curated plotlines, and develop characters that reflect the many intricacies of the human condition. Aside from creating great fictional works of art – providing expertise on matters of national security is also on the agenda for two of the School's creative writing researchers.

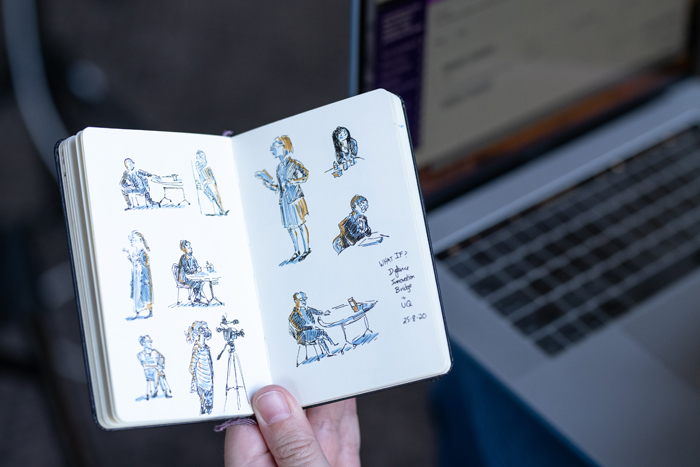

In August 2020, Associate Professor Kim Wilkins and Dr Helen Marshall used creative writing strategies to help launch the Defence Innovation Bridge. This project aims to provide Australia with a new model for innovation by matching defence problems with solutions providers. The School sat down with Kim and Helen to discuss their role in the launch and asked them to share their insights on how creative writing techniques can be utilised to help protect Australia from external threats.

Can you describe The Defence Innovation Bridge?

Sovereign states now face threats from adversaries with unconventional attack technologies, able to harness the power of social networks, encryption, GPS, low-cost drones, 3D printers, and ubiquitous internet and smartphones. In contrast to the agility of many of our adversaries, advanced defence agencies have huge investments in existing land, air and ocean hard and soft infrastructure but are slower to adopt new technologies.

As part of this broader project, WhatIF is a fresh methodology for looking at these problems. We used creative exercises to help researchers in other disciplines ranging from robotics and cybersecurity tell rich and accessible stories based on their expertise. These were designed to inspire innovative solutions to real-world challenges identified throughout the workshop. Whereas design-based thinking may involve a hundred interviews in order to identify and clarify a problem, our skillset—which includes improvisation, creative writing exercises and wargaming—played a vital role in helping interdisciplinary experts to quickly translate their expertise and push their thinking in new directions.

How did you get involved with the project?

We were approached to participate in the project by Cameron Turner who has spent more than twenty years executing innovation and commercialisation strategies. He is guiding a group of MBA students through a semester long bespoke course alongside a defence mentor. Our workshop launched the project and brought in UQ academics alongside defence personnel and industry experts from start-ups and large corporates like Boeing.

What do creative writers bring to the conversation?

Creative writers are trained to think beyond the obvious scenario, towards the disruptive second-order effects or unintended consequences of new technologies. We like to think of it through a metaphor. The human imagination is standard hardware that comes pre-installed at birth. However, most researchers have not updated their software since the age of ten or eleven. This is particularly true of STEM because their disciplinary norms include linear thinking, closed-ended questions, hyperspecialisation, and incremental progression. While these norms have been enormously effective in solving many specialised problems, they can become a liability when experts are faced with collaborating across disciplines or responding to new innovations.

One of the highlights of the day was the matrix game, a low-tech tool for scenario modelling and simulation. In matrix games, players play characters and work together to generate a credible narrative about what they think will happen. While matrix games have been used in defence and cybersecurity in the past, we combined the game with character development exercises which we regularly use as novelists. By thinking about the actors in a particular conflict as characters with histories that inform their motives, their ethics and their decision making, the players both became more invested in the story itself and also came away with a better understanding of the human component. That is, the uptake and use of new technologies are often shaped powerfully by the way real people choose to use them.

Do these strategies translate to the classroom?

The techniques we brought to this workshop are ones we use daily in our teaching and in our writing. Compelling stories come together when characters come into conflict in a specific context—that is a particular setting or time period that shapes the nature of the exchange. What we have done is adapted these techniques to help our experts immerse themselves in a scenario as characters, thereby allowing them to empathise more deeply with the problems that character might face. The exercises were most effective when the workshop participants let go of their preconceived notions and used their imaginations. We piloted this workshop model with the Global Change Institute earlier this year, and will be doing more work for them in the future.

What were some of the key insights?

Some of the best insights emerged around understanding the impact of artificial intelligence and cyberwarfare. For example, hackers in our scenario were able to cause chaos by taking control of the unprotected infrastructure of a state-controlled tsunami warning system to cause chaos for the Australia Defence Forces during their imagined evacuation scenario. All the while a battle to control social media raged on as controlled ‘bots engaged in ‘astroturfing’—using Twitter to give the impression of a groundswell protest movement. By the end of the scenario it was clear that the battlegrounds of the future would be in “grey” zones between states where hybrid and asymmetric warfare may take place. In this space, as author Robert H Latiff says in Future War: Preparing for the New Global Battlefield, “Soldiers will operate under intense time pressures while deluged with information, some of it conflicting." In this environment, success will come down to who can process the most information fastest in order to make the best decisions in an uncertain landscape.

This important collaboration illustrates the impact creative writing research can have on a broad range of industries. Helen and Kim both lecture in the School's Writing Major and are passionate about their craft. If you are interested in finding out more about writing at UQ click here.